With Warhammer 40,000: Darktide now out in the wild, thousands of Rejects have joined the fight in the hive city of Tertium against the hordes of Chaos. Despite the danger, there is still plenty of beauty to marvel at, especially when it comes to level design. To provide a better understanding of what makes Darktide levels tick, Lead Level Designer Joakim Setterberg from Fatshark has much to share.

Human blood and human flesh – the stuff of which the Imperium is made. To be a man in such times is to be one amongst untold billions. It is to live in the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable. This is the tale of those times.

Aside from his role as Lead Level Designer, Setterberg is also part of the Darktide World Team: a multi-disciplinary team of developers that create everything related to environments and missions. With Darktide, Fatshark saw an opportunity to show Warhammer 40,000 through the eyes of the people in this universe. That meant creating a setting that could deliver both on space and place: diverse enough for gameplay and rooted enough for stories. A setting representative of the Imperium of Man and iconic to Warhammer 40,000; the equivalent of Ubersreik or Helmgart from the Vermintide series. The answer was the hive city of Tertium.

Tertium in Warhammer 40,000: Darktide

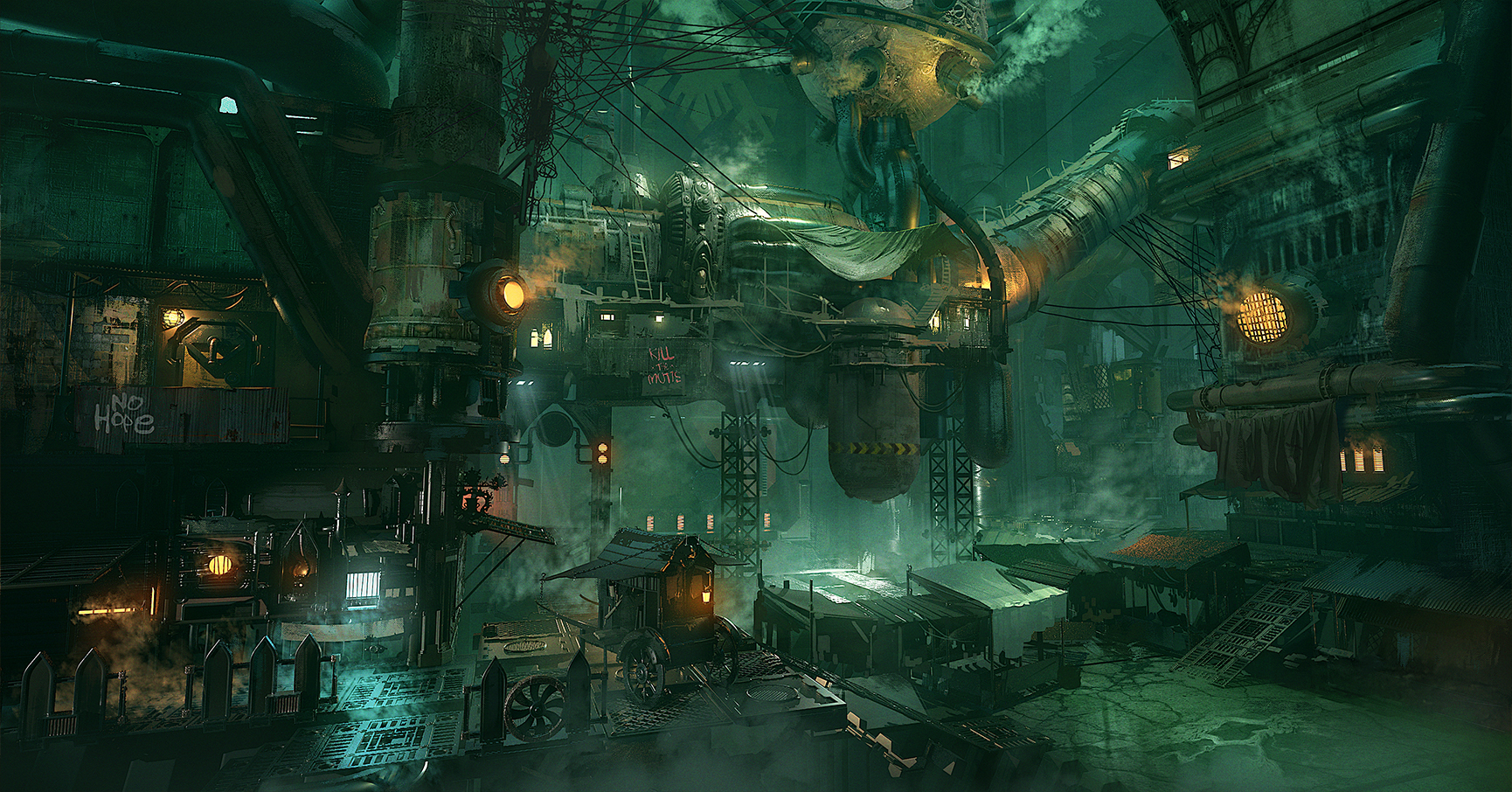

A hive city is not a city as understood through other works of science fiction. It is a factory sprawl, a conglomeration of heavy industries, urban clusters, military facilities and population administration. It is both machine and beast, devouring its uncountable workforce as it produces vital resources for the Imperium’s war efforts. As a supplier of Atoma pattern Leman Russ tanks, Tertium is a jewel in the eyes of the Imperium, but it is also humanity trapped in a cage of industry, all part of an authoritarian system on a constant military footing.

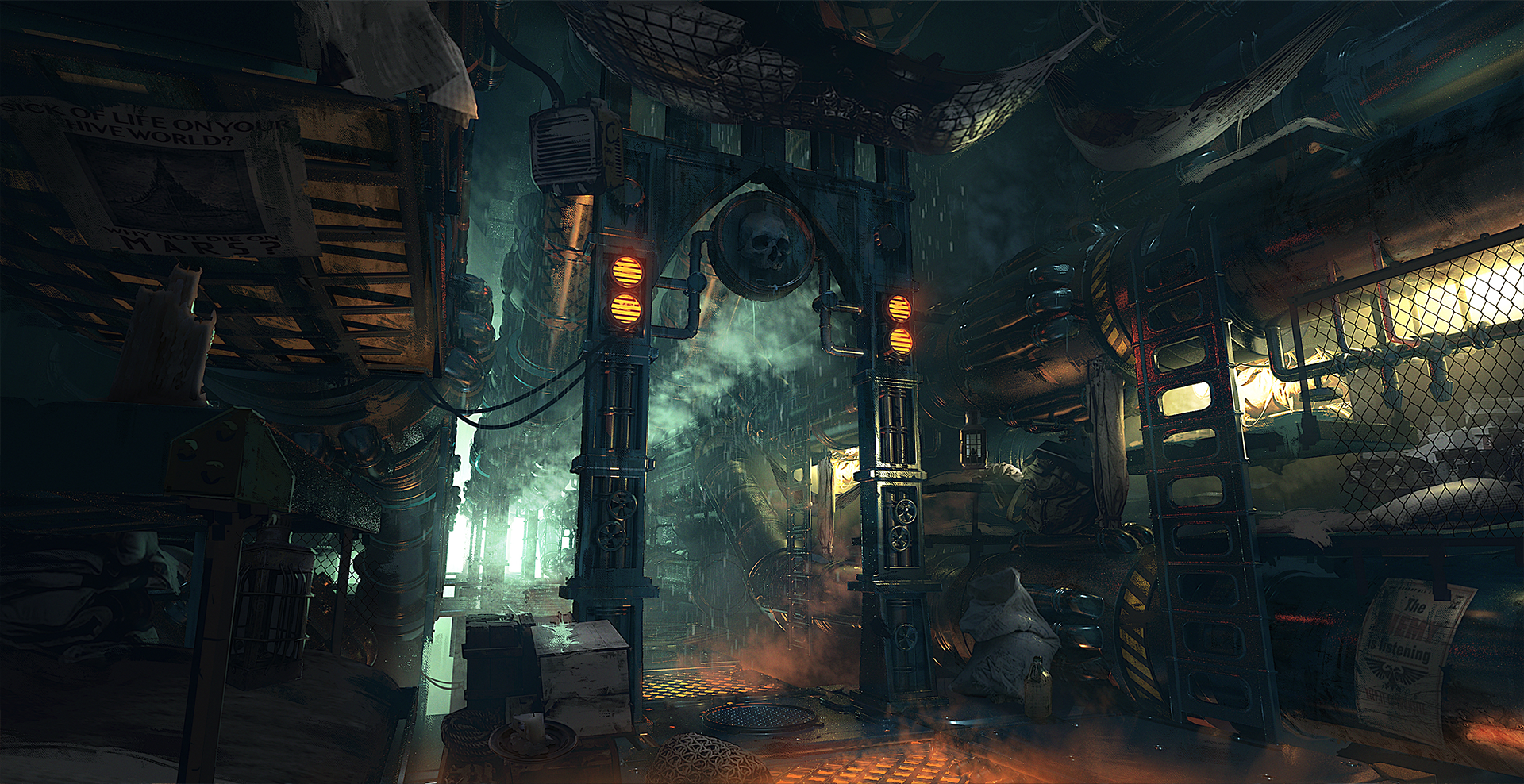

The city is massive in scale, to the point where comparisons to residential grids and layouts make no sense. The best way to appreciate it is to imagine an enormous stranded spaceship or submarine, the size of a continent, with a city built within and between its enormous compartments. It is a three-dimensional construct made out of layers of plasteel, plascrete, rockcrete and ferrocrete, all stacked endlessly upon each other, where concepts of “ground floor” or “sky” serve no purpose to its workforce population. The passing millennia have put the city in a constant state of decay and repair, with older areas buried deep beneath and newer spires piercing the polluted sky. Tertium’s design in Darktide is a place of both epic and small places.

To facilitate the design process, Game Director Anders De Geer came up with an analogy: picture a comfy three-seater couch with skulls and gothic arches, where people have spilt crisps and beer over the years. Now make that a thousand years. Compare that to the couch that has only seen a hundred years of spillage. That is the contrast between old and new in Tertium.

Doing justice to the Warhammer 40,000 aesthetics is, of course, paramount. There is nothing quite like that mix of architecture, religion, time and technology. As a general design rule, the aesthetics are ancient, retro or futuristic but rarely contemporary. Expect holograms and scrolls, spaceships and carts, plasma reactors, archways, gears, tubes, bricks and mortar – all mixed up with religious and Imperial symbolism, candles, skulls and incense.

Taking Cues

Whenever possible, the Darktide team took design inspiration from the miniatures coupled with their own creations, where a tremendous amount of fun work was put into the environmental audio and visuals. Writers were consulted, concepts were created, and research was intense as the lore, miniatures, and fiction was brought together in Fatshark’s vision of the Warhammer 40,000 universe.

Obviously, there were also concessions made along the way. Hive cities are even more extreme than in Darktide; bigger vistas, smaller spaces, more people. For gameplay reasons, it had to strike a fine balance between concept and gameplay, between detail and readability, and between grimdark and dark. The Ogryn is one example – quite a lot of internal testing was done to find a good scale for the Ogryn. Large enough to feel big but small enough to work with the environments, which all had to adapt to the Ogryn and bigger enemies: doorways were widened, floor space was cleared, ceilings raised.

Another is the impact of the hybrid combat with, compared to Vermintide, its increased emphasis on ranged gunplay for players and enemies alike. The Darktide ranged combat loop introduces enemy covers, combat vectors and a need for bigger awareness of enemy positioning, which for the hybrid combat meant a greater degree of player and enemy movement. Players needed ways to counter being pinned down by enemy fire teams behind cover – that meant room for sprinting, vaulting and sliding to accomplish tactical manoeuvres and flanking, switching between suppression and close combat in a matter of seconds. Enemies also needed flanking routes of their own so that they could work together more like an opposing team, with means to navigate around and catch up with players. On top of that, melee combat requires room for dodging and weaving without hitting snags and minuscule collisions.

One of the driving level design principles is that no player, or playstyle, should feel completely at home in all areas of a mission in Darktide. Sightlines offer comfort for long-ranged weaponry, while labyrinthine areas make for fun times for weapons like a flamer. This contrast in topology is essential for player and enemy gameplay, where shifting spaces and situations promote a balanced team composition and allow different team members the time to shine.

Sometimes the same game space will play out quite differently between missions, changing the approach or mission objective. Moving from Vermintide to Darktide gave Fatshark a chance to rework some of the tech and tools for level creation and design. Two things they did were to separate mission logic from the setting, as well as support multiple smaller levels being stitched together to a bigger one. This opened up two possibilities: the team could work in parallel on different areas as well as use the same spaces for different missions; missions could crisscross and compose bigger zones. This will improve the ability to release new content, create a narrative of a coherent city, and enable the team to fix bugs faster than before.

Darktide is a product of labour and love, and Fatshark hopes that it shows – that the game will be the players’ way to experience this fantastic grim dark universe, together with the developers.